London Film Festival

London Film Festival

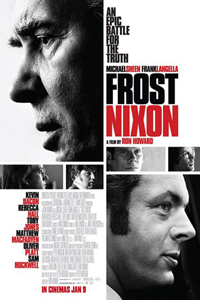

For director Ron Howard and screenwriter Peter Morgan, “Frost/Nixon” was always going to be a tricky beast to handle. A film adaptation of Morgan’s own stage play that was itself very much about the powers of television, the relationship between text, medium and audience has shifted in ways I’m not sure the film’s makers have fully accounted for.

It is one thing to portray a momentous televisual event on the stage, where the intimacy and crackle of live human interaction allows for a very different, and rather more immediate, experience of the proceedings. It is quite another to recreate said event for television’s closer cousin — with the legendary interviews between David Frost and Richard Nixon that form the spine of the narrative widely available, the film has to recreate the spontaneous feel of history in progress, and in doing so, reveal something in a 30-year-old document that we haven’t already seen.

It’s a tall order, and with Morgan’s script hewing closely to its source, Howard responds to it in the manner he knows best: with the most prosaic of visual aesthetics to hand, a doggedly linear approach to storytelling and the spotlight thrust squarely on a reliable pair of actors. The approach only gets him so far. Howard’s hands-off direction makes for an oddly bloodless viewing experience, with a lot of talk standing in for any fresh perspective (or frankly, much of a perspective at all) on the events.

To be honest, we could have seen this coming. It’s difficult to think of a director less-suited to take on the intricate, minutiae-obsessed writing of Peter Morgan than Howard — a director who, even in his finest films, has always been interested in the big picture first, with characters serving history rather than the other way round.

Stephen Frears, a filmmaker preoccupied with the subtleties and ambiguities of intimate human interaction, was a perfect match for Morgan’s “The Queen” (a film that left this viewer personally unmoved, but was far more successful than this film in humanizing the icons at its center). No doubt he could have made “Frost/Nixon” fly too. But Howard is left adrift, particularly in a sluggish first hour where, with the crucial interviews yet to begin, the historical context is painted in broad, CliffsNotes fashion, with a gallery of reconstructed talking-head interviews and distracting lookalike cameos (There’s Diane Sawyer! There’s Swifty Lazar!) in place of significant internal character development.

The latter becomes a more critical problem as the film progresses, and it’s Morgan’s failing as much as Howard’s — the protagonists, for all their force of personality that propels the narrative, rarely emerge as living, breathing people. It’s partly because they’re depicted in such a limited array of contexts — almost always in public, and hardly ever alone — that we never really feel we know them, beyond what we already knew.

There may be some commentary at play here about the media gaze, and it may have worked on stage, but given the closer scrutiny of film, it’s a miscalculation on Morgan’s part. To return to “The Queen,” it wasn’t her skillful re-enactment of Elizabeth II’s public addresses that won Helen Mirren a raft of awards, but the intimate eeriness of her lone encounter with a deer on the Highlands. Here, neither Frost nor Nixon are granted any equivalent moments of vulnerability — Nixon doesn’t even have a scene alone with his wife, for crying out loud.

There may be some commentary at play here about the media gaze, and it may have worked on stage, but given the closer scrutiny of film, it’s a miscalculation on Morgan’s part. To return to “The Queen,” it wasn’t her skillful re-enactment of Elizabeth II’s public addresses that won Helen Mirren a raft of awards, but the intimate eeriness of her lone encounter with a deer on the Highlands. Here, neither Frost nor Nixon are granted any equivalent moments of vulnerability — Nixon doesn’t even have a scene alone with his wife, for crying out loud.

This narrowness of focus inevitably constricts the performances, though they will certainly remain the most discussed aspect of the film. While Langella’s work lacks the invention or audacity of Anthony Hopkins’s interpretation in Oliver Stone’s 1995 “Nixon,” awards talk will likely continue to circle around his broadly entertaining inhabiting of Richard Milhous Nixon, a precise assemblage of vocal and physical tics executed with a faintly tongue-in-cheek quality that is slightly (albeit happily) at odds with Howard’s rather po-faced approach.

Langella has the gift of creating mournful comedy out of unscripted reactions (where Morgan’s one-liners can land a little too heavily). In a lovely moment, the actor’s simple, non-committal “hmm” after Nixon learns that Frost dated African-American singer Diahann Carroll speaks complex volumes about the man and his values.

As the tone of the scenes grows more confrontational, however, the performance grows markedly less interesting. Leading with his impressive, booming approximation of the Nixon voice, Langella is allowed to actively chew scenery and the performance becomes increasingly detached from the overall work.

In a crucial scene chocked full of potential Oscar clips, he rants furiously (and drunkenly) down the phone to Michael Sheen’s Frost, tightly framed and lit in an expressionist fashion. It’s one of the few occasions Howard openly embraces the film’s stage roots, and it’s certainly riveting in isolation, but it has little bearing on the language of the film.

In a crucial scene chocked full of potential Oscar clips, he rants furiously (and drunkenly) down the phone to Michael Sheen’s Frost, tightly framed and lit in an expressionist fashion. It’s one of the few occasions Howard openly embraces the film’s stage roots, and it’s certainly riveting in isolation, but it has little bearing on the language of the film.

Both Langella and Sheen’s characterizations, in fact, are writ rather too large, neither actor making much effort to dial down the scale of their work from their stage incarnations to accommodate the proximity of the camera. However, Sheen (the film’s true lead, whichever way you slice it) comes off worse than Langella. He captures Frost’s initial smarminess with some relish — coming dangerously close to mugging at times — but the performance quickly becomes one-note, offering neither the magnified subtlety or shading to make Frost a compellingly flawed hero, nor the firepower to match Langella’s in the film’s showy set-pieces.

Surprisingly, considering they are both recreating their stage roles, Langella and Sheen struggle to build much chemistry between the pair. That’s partly because a significant portion of the film is devoted to business between a cast of under-drawn supporting characters: Kevin Bacon, as Nixon’s conflicted aide Jack Brennan, comes off best; the gifted Rebecca Hall, stuck in the wholly decorative role of Frost’s girlfriend Caroline Cushing, rather worse. The greater problem, however, is that the film reveals so little of their inner lives that their interaction lacks any discernible subtext beyond the “quest for the truth” that the film’s marketing so pompously foregrounds.

For all the intelligence and polish on display here, “Frost/Nixon” ultimately proves no more insightful a portrait of Richard Nixon (or David Frost, for that matter) than the original interviews themselves. Near the end of the film, in a speech lifted directly from the original play, Sam Rockwell’s Jim Reston tells us, “The greatest sin of television is that it oversimplifies, diminishes…great complex ideas, whole careers, become reduced to a simple snapshot.”

Well, in some respects, film and television are not all that different. It’s an irony that Howard and Morgan obviously did not intend and certainly should have taken to heart before embarking on this coldly unilluminating film.